Kyrgyzstan, and more broadly Central Asia, is beginning to experience the effects of climate change firsthand, leading to severe water shortages in the lowlands and neighboring countries, as well as a deficit in energy production from hydroelectric plants. Kyrgyzstan is home to a large proportion of nomadic communities who are witnessing environmental changes firsthand, especially in the valleys and at high altitudes. Recurrent droughts are becoming longer, glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates, and green pastures are becoming increasingly scarce. In a country with intensive livestock breeding, the remaining grasslands are insufficient, and overgrazing is accelerating soil degradation—new challenges that these communities must adapt to.

The volume of the region's mighty high-altitude rivers is also decreasing due to drought and a lack of snow and rainfall in the mountains, which endangers electricity production and further reduces water flow downstream. One such river is the Naryn, which has the largest hydroelectric plants along its route in the region. The Naryn River flows into the Syr Darya, a crucial water source for irrigating the agricultural heartland of Central Asia, which eventually empties into the Aral Sea—or what remains of it. At the current pace, Central Asia could easily become a hotspot for water and energy conflicts. Low-intensity conflicts already occur between Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Kyrgyzstan and more generally Central Asia start to experience the effects of climate change first hand causing severe water shortages in the low lands and neighbouring countries and a deficit of energy produced by hydro power plants. Kyrgyzstan consists of a very large propotion of nomadic communities who can witness of the environmental changes they witness down the valleys and at high altitude. Recurrent periods of drought are longer and longer, glaciers are melting at a speed never witnessed before, and green pastures become more difficult to find. In a country of intensive animal breeding, the remaining grasslands are insufficient and over grazing accelerates soil degradation. All new challanges that the communities have to adapt to. The volume of the mighty high altitute rivers is also decreasing due to drought and lack of snow and rain in the mountains, endangering the production of electricity and further reducing the water flow of the rivers downstream. One of those rivers is the Naryn river which has the largest hydro power plants along its route in the region. The Naryn river flows into the Syr Darya which is crucial for irrrigation of the agriculture heartland of Central Asia and who eventually flows into the Aral Sea, or at least what is left of it. At the present pace, Central Asia could easily become a future hotspot of water and energy conflicts. Low intensity conflicts already occur between Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Asambek, 60 years, has been a shepherd since his youngest age. Stays nearly 3 months at an altitude of 4,000m with his herd of 750 sheeps and his younger brother to help him. Arabel, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Sheperds bring their animals higher and higher up the mountains in search of grassland. Years of drought paired with land degradation due to over-grazing have severely affected available grasslands for the millions of livestock being raised in Kyrgyzstan. Barskoon valley at 3,750m altitude, Issyk Kul region, August 2021

Chu river flowing through an empty Ortotokoy reservoir. Due to a prolonged and recurrent drought in Central Asia and in particular in mountanious Kyrgyzstan, rivers and their water volume have decreased dramatically , jeopardizing the production of electricity and agriculture yield in the countries further down the rivers. Ortotokoy reservoir, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Arabel melted glacier. Local shepherds have witnessed retrieving glaciers during the past decennia with a clear acceleration during the past years. Arabel, 4,200m altitude, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Babur and his children staying for about 3 summer months at high altitude along the shore of Son Kul Lake where they breed horses and sheep. During the remaining of the year they live down the valley near the Naryn river. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Horse milk collection, summer pastures along Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

People crossing the Naryn river in Kyzyl Beyzit after visiting relatives. Kyzyl Beyzit is and area that has been flooded since the eighties when dams were constructed on the Naryn River. The remaining village is locked in and only accessible by boat and donkey or horse accross the river. About 300 people live there. The hydro electrical power station on the Naryn river and the Toktogul reservoir are crucial for Kyrgyzstan's energy needs, but with longer and recurring periods of drought it becomes impossible to cater for an ever increasing population. The Naryn river, which in Uzbekistan will become the Syr Daria river and eventually flow into the Aral Sea, has an ever decreasing volume. Further accelerating the complete disappearance of the Aral Sea few thousand km away. Kyzyl Beyzit, Jalalabad region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Kyzyl Beyzit is and area that has been flooded since the eighties when dams were constructed on the Naryn River. The remaining village is locked in and only accessible by boat and donkey or horse accross the river. About 300 people live there. The hydro electrical power station on the Naryn river and the Toktogul reservoir are crucial for Kyrgyzstan's energy needs, but with longer and recurring periods of drought it becomes impossible to cater for an ever increasing population. The Naryn river, which in Uzbekistan will become the Syr Daria river and eventually flow into the Aral Sea, has an ever decreasing volume. Further accelerating the complete disappearance of the Aral Sea few thousand km away. Kyzyl Beyzit, Jalalabad region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Livestock owners at their high altitude summer retreat where they find pastures for their livestock. Livestock is the main subsistance in Kyrgyzstan. Climate change, droughts and soil degradation are affecting their livelihood at unprecedented levels in the past years. Ak Tal, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Shepherd carrying a black sheep, Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Sheperds bringing their sheeps to graze in what should be a filled reservoir of a hydro power plant on the Chu river. Due to a prolonged and recurrent drought in Central Asia and in particular in mountanious Kyrgyzstan, rivers and their water volume have decreased dramatically , jeopardizing the production of electricity and agriculture yield in the countries further down the rivers. Ortotokoy reservoir, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Asambek, 60 years, has been a shepherd since his youngest age. Stays nearly 3 months at an altitude of 4,000m with his herd of 750 sheeps and his younger brother to help him. At this altitude only sheep and yak can survive. He has been coming here for the past 8 years because few people come and he can find more water and grass. Before he would never go much higher than 3,000m but during the past years, grass and water have become scarce at lower altitude and in the valleys due to the recurrent drought and soil degradation. As a shepherd he is also the first in line to witness the melting and disappearance of the glaciers. Arabel, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Arabel location at 4,000m altitude where the remains of glaciers are seen on the background. Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Horse breeders collecting milk at their high altitude summer camp. Mountains above Eki Naryn, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Child on top of a concrete yurt build travellers passing through Son Kul Lake 3,000 above sea level and only accessible between end of June and September. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Drinking fresh horse milk, a very praised delicacy in Central Asia. Ak Tal, Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

A boy from the Naryn region milking the few cows owned by his family. Livestock is the main subsistance in Kyrgyzstan. Climate change, droughts and soil degradation are affecting their livelihood at unprecedented levels in the past years. Ak Tal, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

High altitude road with melting glaciers on the background. Climate warming paired with longer periods of drought have in the past decennia accelerated the disappearance of Kyrgyz and Tajik glaciers provoking land slides, floods and destruction of entire communities. Road to the Kumtor gold mine, 4000m altitude, Barskoon valley, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

A family staying for about 3 summer months at high altitude along the shore of Son Kul Lake where they breed horses, keep several hundreds sheep and run a small guesthouse for passing travellers. During the remaining of the year they live down the valley near the Naryn river. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Toktogul Reservoir on the Naryn river showing alarming low levels following persistent droughts in Central Asia. The hydro electrical power stations on the Naryn river and the Toktogul reservoir are crucial for Kyrgyzstan's energy needs, but with longer and recurring periods of drought it becomes impossible to cater for an ever increasing population. The Naryn river, which in Uzbekistan will become the Syr Daria river and eventually flow into the Aral Sea, has an ever decreasing volume. Further accelerating the complete disappearance of the Aral Sea few thousand km away. Toktogul Reservoir, Kara Kul, Jalalabad region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Horses, summer pastures along Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Shepherds reaching high grounds in search of grass for their livestock. Due to recurrent drought increased by climate change and soil degradation due to over grazing, it becomes more difficult to feed livestock even during the summer months when high altitude pastures are accessible. Moldo Ashu Pass, Ak Tal, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Ramazan, 16 years old, staying with his family during the summer months at high altitude in search of green pastures for their livestock. Livestock is the main subsistance in Kyrgyzstan. Climate change, droughts and soil degradation are affecting their livelihood at unprecedented levels in the past years. Ak Tal, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Livestock owners at their high altitude summer retreat where they find pastures for their livestock. Livestock is the main subsistance in Kyrgyzstan. Climate change, droughts and soil degradation are affecting their livelihood at unprecedented levels in the past years. Ak Tal, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Toktogul Reservoir on the Naryn river showing alarming low levels following persistent droughts in Central Asia. The hydro electrical power stations on the Naryn river and the Toktogul reservoir are crucial for Kyrgyzstan's energy needs, but with longer and recurring periods of drought it becomes impossible to cater for an ever increasing population. The Naryn river, which in Uzbekistan will become the Syr Daria river and eventually flow into the Aral Sea, has an ever decreasing volume. Further accelerating the complete disappearance of the Aral Sea few thousand km away. Toktogul Reservoir, Kara Kul, Jalalabad region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

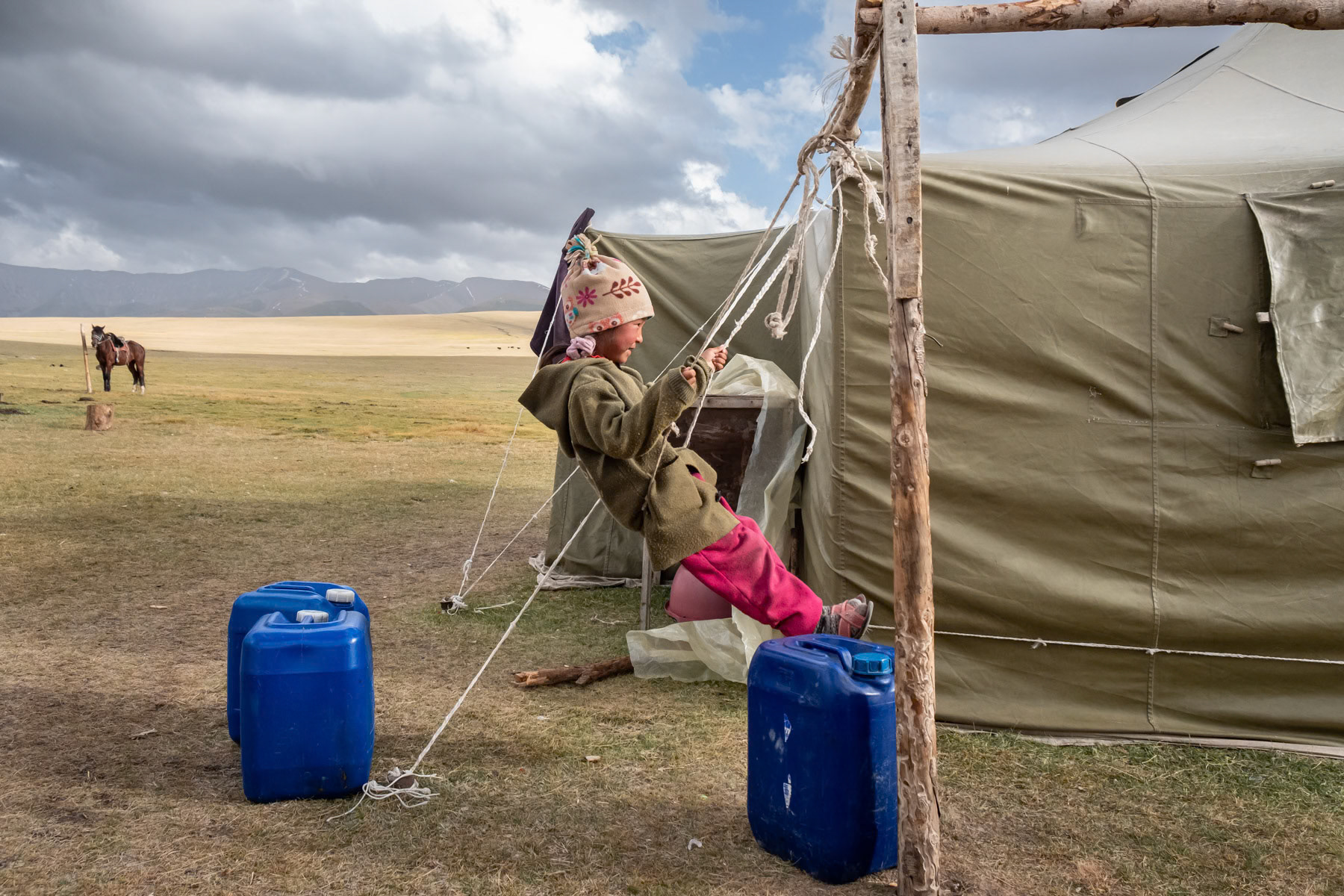

Child playing at a yurt camp where her family lives for 3 months during the summer in search of green pastures at high altitude. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Workers carrying a haystack. The price of animal feed has substantially increased due to a persistent drought affecting all regions of Central Asia, including high altitude locations in Kyrgyzstan. Eki Naryn, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

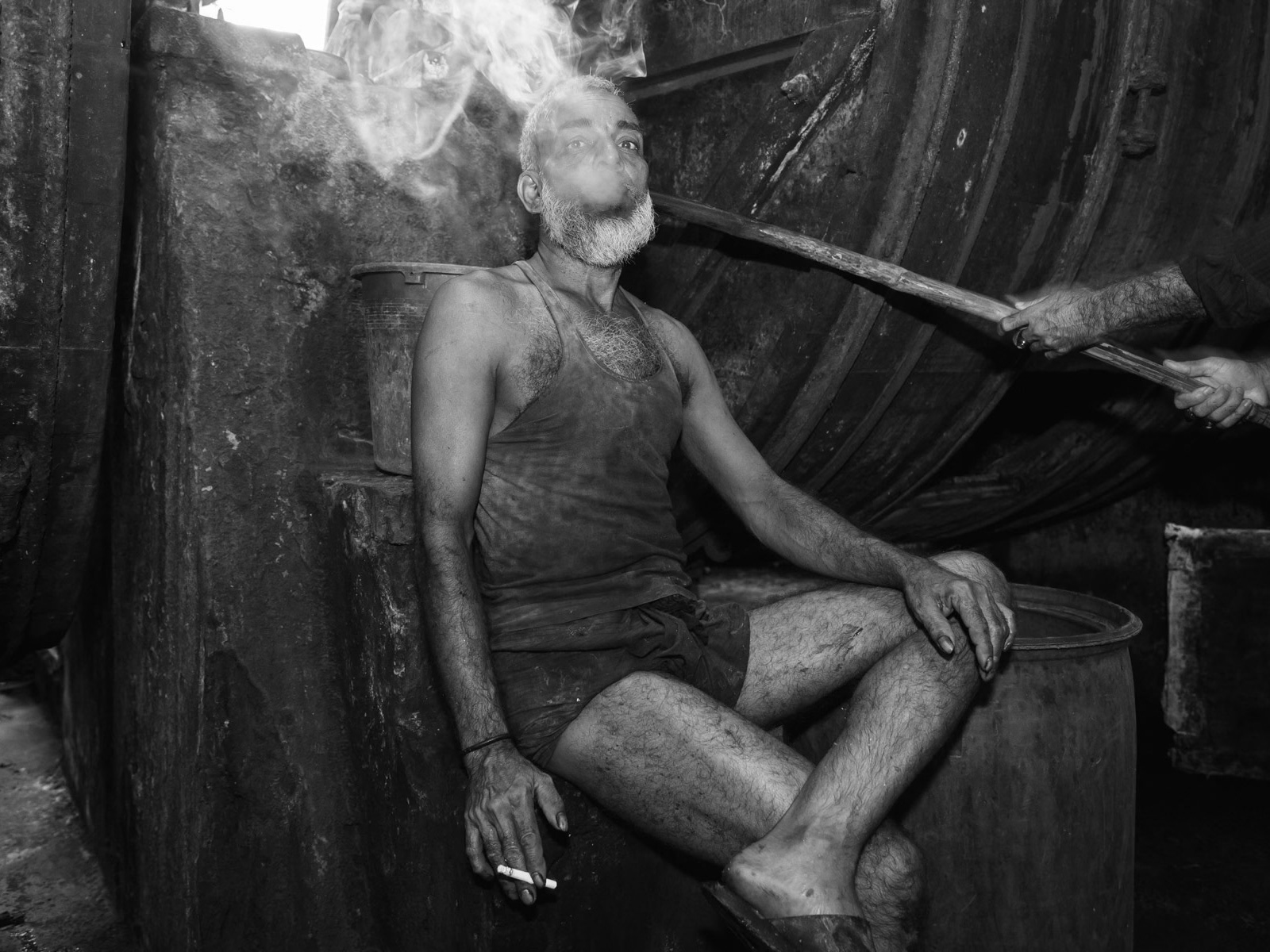

Asambek, 60 years, has been a shepherd since his youngest age. Here in his shelter where he stays nearly 3 months at an altitude of 4,000m with his herd of 750 sheeps and his younger brother to help him. At this altitude only sheep and yak can survive. He has been coming here for the past 8 years because few people come and he can find more water and grass. Before he would never go much higher than 3,000m but during the past years, grass and water have become scarce at lower altitude and in the valleys due to the recurrent drought and soil degradation. As a shepherd he is also the first in line to witness the melting and disappearance of the glaciers. Arabel, Issyk Kul region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Children staying with their parents for about 3 summer months at high altitude along the shore of Son Kul Lake where they breed horses and sheep. During the remaining of the year they live down the valley near the Naryn river. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Local horse breeders training a sequence of 'horse wrestling'. Son Kul Lake, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Kyzyl Beyzit is and area that has been flooded since the eighties when dams were constructed on the Naryn River. The remaining village is locked in and only accessible by boat and donkey or horse accross the river. About 300 people live there. The hydro electrical power station on the Naryn river and the Toktogul reservoir are crucial for Kyrgyzstan's energy needs, but with longer and recurring periods of drought it becomes impossible to cater for an ever increasing population. The Naryn river, which in Uzbekistan will become the Syr Daria river and eventually flow into the Aral Sea, has an ever decreasing volume. Further accelerating the complete disappearance of the Aral Sea few thousand km away. Kyzyl Beyzit, Jalalabad region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021

Women take care of all household activities and collect milk several times a day from the horses and cows. Entire families will live for up to 3 months in their yurt camp high up in the mountains in search of green pastures. Son Kul Lake, Naryn region, Kyrgyzstan, August 2021