Migration from El Salvador is shaped by a complex legacy of civil war, deep social inequalities, violence, and climate change. El Salvador, the smallest country in Central America with a population of 6.4 million, is also the most densely populated in the region. Over the past three decades, a stagnant post-conflict economy, frequent natural and climatic disasters, and escalating violence have driven increasing numbers of people to leave. The majority of Salvadorans migrate to the United States, where nearly 1.5 million El Salvadorans now reside.

Social unrest, which had been building for decades, escalated into open conflict by the mid-1970s, culminating in a brutal civil war from 1980 to 1992. During this period, the United States played a pivotal role, providing significant military aid, funding, and training to the right-wing government. The war displaced about one-fifth of the population, and approximately 75,000 people were killed, with thousands more tortured or disappeared. According to a U.N. Truth Commission report, over 85% of these atrocities were carried out by government forces supported by the U.S. After the war, despite the peace agreement, the unequal economic system largely remained unchanged, perpetuating worsening living conditions and expanding inequalities. This economic structure has been artificially sustained by remittances sent by the growing number of Salvadoran migrants abroad.

Today, violence levels in certain areas are even higher than during the civil war, affecting entire communities. The overwhelming majority of victims are poor, working-class Salvadorans who live in some of the most dangerous neighborhoods, unable to afford private security. This situation continues to drive a large flow of Salvadorans leaving the country in search of safety and stability.

In addition to violence, climate change and natural disasters are significant drivers of migration. Recurrent droughts and rising temperatures have severely impacted agrarian practices, forcing large portions of the rural population to move to cities and, eventually, abroad. As a major coffee producer, El Salvador has seen increasing challenges in cultivating coffee at traditional altitudes between 800 and 1,200 meters. Due to rising temperatures, coffee is now being grown at higher altitudes, sometimes above 2,000 meters, leading to higher production costs and diminishing land availability. With falling global coffee prices, many Salvadorans are abandoning coffee farming, as moving to higher altitudes is not a viable option for all involved in the industry.

Thus, while people leave, their memories and the ongoing struggles remain deeply etched in the fabric of Salvadoran society.

Tomasa Lopez in front of a mural depicting a scene of the Sumpul river massacre. Tomasa from Arcatao witnessed when in 1980 the town and surrounding villages were attacked by government military forces and villagers including children would be randomly executed and hung from trees. Her mother and sister were killed, she fled while being pregnant with her 2 nieces and 2 nephews to the mountains and joined the resistence Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). In 1982 her nieces and nephews were abducted by the military and she lost all track. They were eventually tracked by Pro Busquera, an organisation searching relentlessly for dissapeared children during the civil war, in Spain, France and the US in 1996. They had been sold and adopted through a well established system during the war operated by government military forces and groups in the US and Europe. They have since been reunited at several occasions but not yet in El Salvador. Arcatao, Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

A local music band visiting villages before Easter celebrations, El Almendro village, El Salvador, April 2019 Migartion from El Salvador is shaped by a legacy of civil war, deeply rooted social inqualities, violence and climate change. El Salvador and its population of 6.4 million is the smallest Central American country, yet the most densely populated of the region. A post-conflict stagnant economy, natural and climatic disasters and high levels of violence have pushed growing numbers of people to leave over the past 3 decades. Most by far make their way to the U.S. where nearly 1.5 million El Salvadorans live. Persistent social unrest erupted into open conflict by the mid-1970s, culminating in a bloody civil war between 1980 and 1992. The U.S. played a pivotal role by providing enormous levels of funding, military aid, advisors and training to the right-wing government in power. The conflict displaced roughly one fifth of the population and some 75,000 people were killed during the war in addition to the thousands who were tortured and disappeared. More than 85% of these atrocities were committed by government troops supported by the U.S., according to a U.N. Truth Commission report. After the war the unequal economic system remained basically the same resulting in worsening living conditions and widening inequalities in an economy artificially sustained by remittances from the ever growing Salvadoran migration abroad. Today, levels of violence are even higher than during the civil war in certain areas and have affected entire communities. The overwhelming majority of victims being the poor working class Salavadorans who must live and conduct their lives in some of the most dangerous areas and who cannot afford private security companies to protect them. This situation contributes at maintaining a large flow of Salavadorans leaving the country. Climate change and natural disasters is also a reason why Salvadorans leave there country. Repetitive droughts and rising temperatures have substantially altered agrarian practices pushing large portions of the rural population towards the city and eventually immigration. El Salvador is a large coffee producer, in recent years coffee producers have more and more difficulties to cultivate the coffee at what were once normal altitudes between 800 and 1200m. Because too high temperatures coffee is being cultivated at higher and higher altitude, even above 2000m with as result higher production costs and less available land. With falling world prices, more and more Salvadorans have to abandon coffee production as moving higher in the mountains is not possible for all involved in the coffee production. People leave, memories stay.

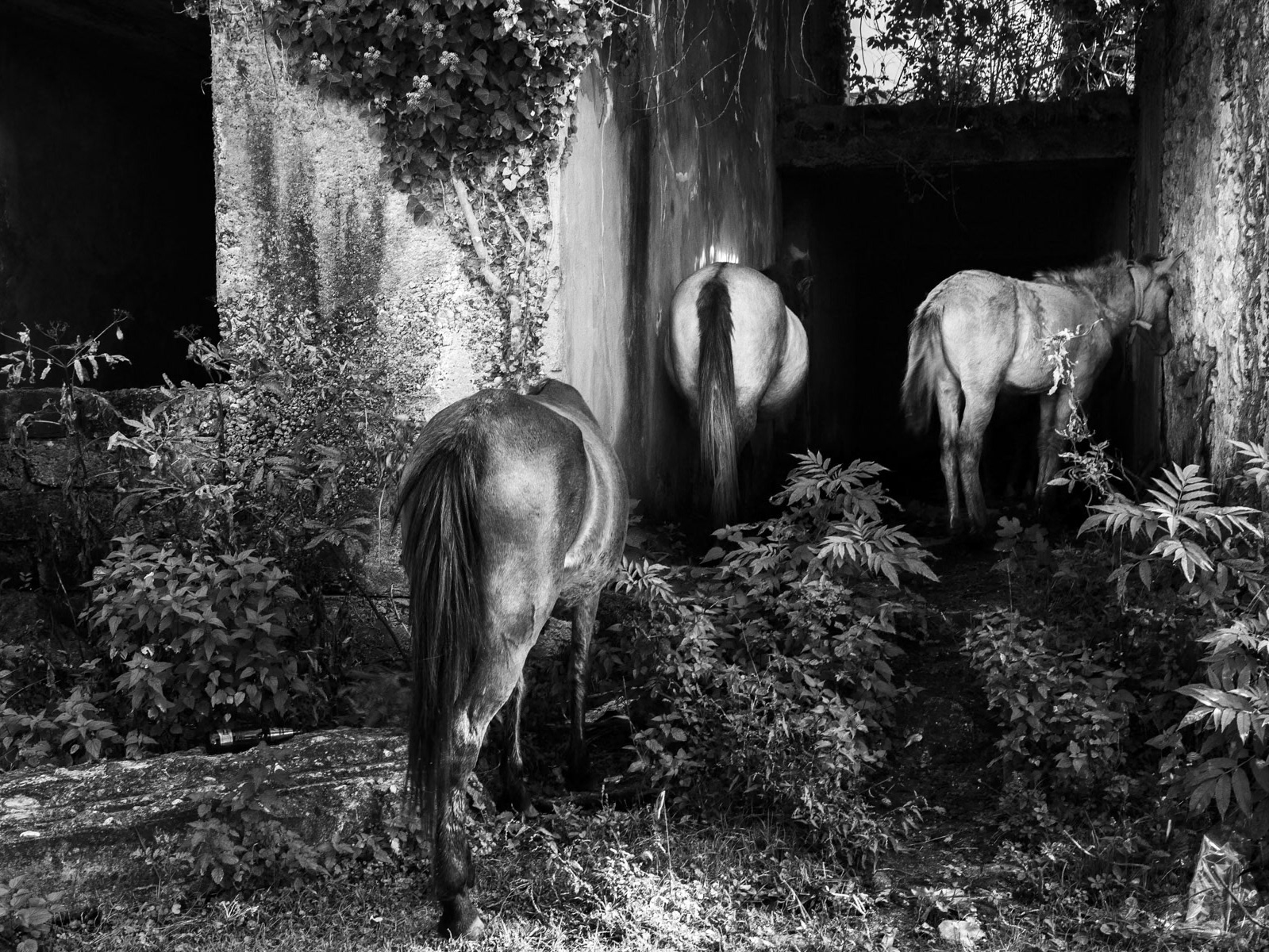

Arcatao a stronghold of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), El Salvador, April 2019

Magdaleno Serrano, 77 years, has a daugher from a first marriage whom he left with villagers when she was 5 years old and when he joined the guerilla movement. He saw her a last time in 1984 when she was seven before she was taken for adoption and ended up in the US. She was found 25 years later and came for the first time to El Salvador in 2009 when she was 32 years. He went to see her in the US in 2017. She was found and matched through Pro-Busquera, an organisation seeking the hundreds of children that have been abducted and dissapeared in adoption schemes towards the US and Europe. Arcatao, El Salvador, April 2019

High altitude coffee plantation. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. Coffee production is one of the most important export commodity for El Salvador. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

A coffee producers and his high altitude coffee harvest ready to be sold as exclusive quality. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

Access road to high altitude coffee plantations in the El Pital Mountains. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

El Almendro, El Salvador, April 2019

Manual Lopez is Salvadorian but living in a village along the border that is now part of Honduras. The El Salvadorian President gave by decree in 1979 several villages in Chalatenango to Honduras that were used as guerilla bases to fight the right-wing government. This move also isolated the guerilla of the hinterland.The territory was never returned and remains a part of Honduras as confirmed by the International Court in The Hague. Zazalapa border village in Honduras, April 2019.

Easter preparations, where enire streets are covered with religious figures and symbols made with coulored salt. The path of salt will guide the people to the church on Easter day. Antiguo Cuscatlan, San Salvador, El Salvador, April 2019

Easter preparations, where enire streets are covered with religious figures and symbols made with coulored salt. The path of salt will guide the people to the church on Easter day. Antiguo Cuscatlan, San Salvador, El Salvador, April 2019

Easter in Antiguo Cuscatlan near San Salvador, El Salvador, April 2019

High altitude coffee plantation. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. Coffee production is one of the most important export commodity for El Salvador. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

High altitude coffee plant. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. Coffee production is one of the most important export commodity for El Salvador. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

A coffee producers and his high altitude coffee harvest ready to be sold as exclusive quality. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

High altitude coffee harvest ready to be sold as exclusive quality. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019

Map of El Salvador, Arcatao school, Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) meeting in Arcatao for the election of town councils. Arcatao, El Salvador, April 2019

A woman from Arcantao recounting the tough years during the civil war between 1980 and 1992 in El Salvador. The area around Arcatao has been the scene of numerous masacres and war crimes carried out by govrnment dead squads supported by the U.S. The resistence and guerilla had established themselves in the surrounding mountains along the border with Honduras. Arcatao, Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

Easter celebration, San Salvador, El Salvador, April 2019

Maria Marchiana Echeverria, 83 years, had to flee in the mountains when the region was attacked by right-wing military dead squads in 1980. She fled because she was accused of being part of the guerilla, her husband and 5 boys were assasinated by the military. She managed to escape in the mountains with her 3 surviving daughters were she will stay for 12 years before returning to Arcatao. During the first 3 months her children were about to die because the lack of food, water and shelter. Hardly able to survive she gave 2 of her daughters (Justa and Carolina) to a religious organisation that put them for adoption in Guatemala. She traced them only 22 years after the war had ended in 2014. When returning to Arcatao in 1991, the village was completely destroyed, villagers were still being tortured by the military, where most torture and killings of suspected guerrilla's took place in the church. Even children would be tortured to denounce gueriilla members. The perpetrators of the massacres and war crimes in Arcatao and the wider region have never been put on trial to date. Arcatao, El Salvador, April 2019

Easter preparations, where enire streets are covered with religious figures and symbols made with coulored salt. The path of salt will guide the people to the church on Easter day. Antiguo Cuscatlan, San Salvador, El Salvador, April 2019

Portrait of Archbishop Oscar Romero, an outspoken defender of human rights and critic of assasinations and torture amid a growing conflict between left-wing groups and right wing government forces. He was murdered by extreme right-wing dead squads during mass celebration in March 1980. Church of Arcatao in Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

Victims of the civil war that raged between 1980 and 1992 in El Salvador. Church of Arcatao in Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

Tomasa Lopez from Arcatao witnessed when in 1980 the town and surrounding villages were attacked by government military forces and villagers including children would be randomly executed and hung from trees. Her mother and sister were killed, she fled while being pregnant with her 2 nieces and 2 nephews to the mountains and joined the resistence Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). In 1982 her nieces and nephews were abducted by the military and she lost all track. They were eventually tracked by Pro Busquera, an organisation searching relentlessly for dissapeared children during the civil war, in Spain, France and the US in 1996. They had been sold and adopted through a well established system during the war operated by government military forces and groups in the US and Europe. They have since been reunited at several occasions but not yet in El Salvador. Museum in memory of the victims of the massacres in the region of Arcatao and Sumpul, Chalatenango, El Salvador, April 2019

Villagers waiting for the priest to start the Sunday mass. The polulation of Corazor are Salvadorian but the village is now part of Honduras. The El Salvadorian President gave by decree in 1979 several villages in Chalatenango to Honduras that were used as guerilla bases to fight the right-wing government. This move also isolated the guerilla of the hinterland. The territory was never returned and remains a part of Honduras as confirmed by the International Court in The Hague. Corazor village in Honduras, April 2019.

High altitude coffee plantation. Due to climate change and rising temperature coffee producers plant the coffee at higher altitudes sometimes higher than 2000m what would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. El Pital mountains, Los Planes in San Ignacio region, El Salvador, April 2019